The Unbound

email:jenniferredmond@proton.me jenniferredmond@me.com

Unbound is a showcase for personal and collaborative work initiated and collated by Jennifer Redmond.

It is a platform for artists and writers to connect mingle, and to collaborate with one another.The idea is to blend artforms and expand our range of compositional processes.

Unbound seeks diverse voices and dynamic styles – courting the experimental in writing, moving-image and sound.

It is a platform for artists and writers to connect mingle, and to collaborate with one another.The idea is to blend artforms and expand our range of compositional processes.

Unbound seeks diverse voices and dynamic styles – courting the experimental in writing, moving-image and sound.

BIOGRAPHY

Jennifer Redmond is a multidisciplinary, artist, writer and filmmaker living in Cork. She has published works in The Madrigal, wearecollected.com in mink.run, The World Transformed Anthology, and critical theory in The Visual Artists Newssheet. Her writing, filmmaking and art practice connect in experimental and hybrid forms. She has made and shown three poem films at The Ó Bhéal Poetry Film Festival and has broadcast work live on national radio.

She is an associate of Parity Studios UCD having been the Neville Johnson scholar 2016. Her research was carried out in collaboration with Dr Tony Veale (Computer Science) and THe Department Of Veterinary Science explored the evolution of human consciousness and human-machine entanglement through the interactive operations of an online social media bot and using the ideation and philosophical figuration of Parasites. She holds a B.Ed(Hons)TCD and her master's in Art and Process was from MTU in 2014. She has published poetry, in The Madrigal, The World Transformed Anthology, and non-fiction in the Wild Atlantic Way non-fiction competition. Art/film critique in; wearecollected.com, in mink. run, and in The Visual Artists Newssheet, and fiction in Swerve Magazine. She specialises in performative lectures and audio-essay; performing in UCC,(2017)UCL London(2017),UCD(2017),Uillinn Arts Centre (2017)The Guesthouse Cork(2022) RTE Radio1(Keywords) Dublin Digital Radio (2023) and at The 2nd Symposium on Digital Art in Ireland UCC June 2024 in UCC. She has shown poetry films at the O Bhéal Winter Warmer Festival in 2022 and 2023. In any medium, her work leans towards transgressive experimental and hybrid ideologies, queer ethics and quantum aesthetics.

She is especially interested in collaborations with individuals from any discipline believing that the creations of an individual are limited and limiting, that notions of boundaries and categories are human constructs and of little use to current and future generations of life on this planet

Scarecrow is a poetry film. A testimonial to the lived experience of many women and to how they might view the sum of their lives on this planet. It is also a commentary on Capitalism and the human use of land for financial gain; The scarecrow is a metaphor for the feminine, the elder wise woman who acts as an augur for a precarious future, for the disintegration of human civilization.

Scarecrow

Bum passing in the street cat calls…

‘Hey Hey Hey, pretty lady–dance with me?’

I’m thinking–

that hasn’t happened in a while

why it’s the last straw!

Vexed

Thinking–

he must be blind/lonely/desperate…

must not be invisible today

better pull in that sagging gut

–chuffed

‘Give you gold for your dust’ he says

I’m thinking –he’s mad

still every girl wants to be a princess/queen–

mindless!

Not so much though, not lately–

I’m thinking…

So no, I won’t dance with you,

it’s much too late in the Autumn–

all that grain to watch

and crows…

crowds of crows to scare

murders of crows everywhere.

When you think about it,

there is so much grain,

and yet not enough…

never enough of the golden stuff

I’m thinking–

Can’t believe I’ve spent

incalculable hours in gratuitous toil

nose to the grindstone

and never learnt to separate

wheat from the chaff

to daily pound–make my own bread

I’m thinking–

truth is, we should be eating less bread

and understanding that

work outlasts lifetimes–even the unpaid kind

I forget if…If?

These are my hands working

or the projections of some other

demon, desire or drive

perpetually in need

of the gifts of our mother. I’m thinking…

Is our touchstone changing colour?

ASEMIC WRITING

Asemic writing is a form of writing that is open- semantic, wordless and withoyt conventionally understood meaning. It’s non-specificity means that the reader inferrs their own meaning and authorial intent is incidental to the process. The practice of asemic writing fuses text and image but then dispenses with the rigors of formal script by encouraging arbitary and subjective interpretations. In fact the very intention of making no sense in the usual ways, is central to the practice.The text may be understood symbolism inferred and meanings collaboratively explored, in which case the ‘reader’ is the co-creator of the work thus usurping the tryanny of the artist

Asemic or pansemic writing originated in the late 1990’s as part of the visual poetry movement where practicioners explo/author.re sub-verbal and sub-letteral forms of writing. It is practiced as an intentional art/poetry practice that allows the poet to move byond words and the artist to switch off the brain and to indulge only gesture. It can often be practiced while listening to music.

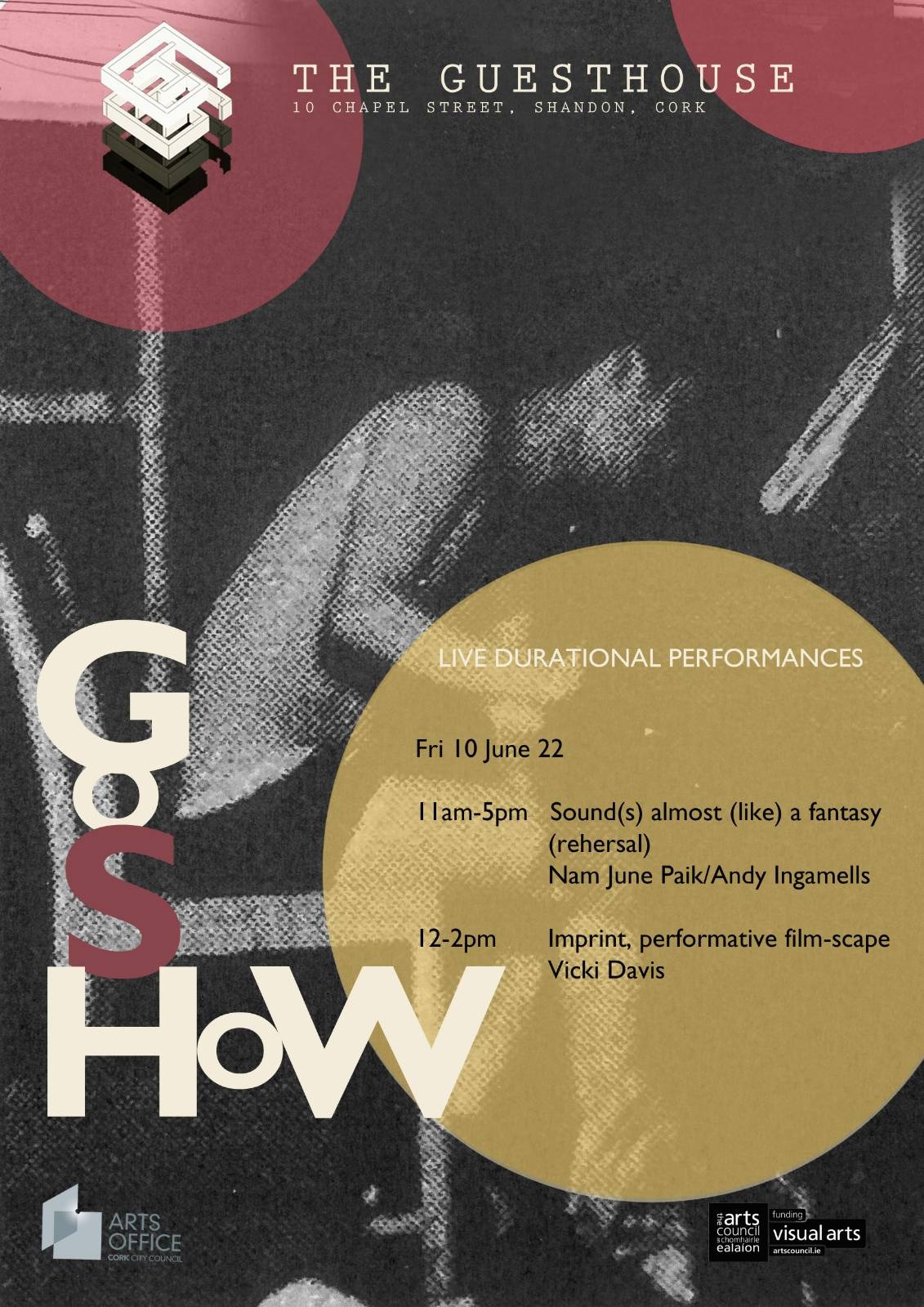

Throughout 2022 and as an artist in residence at the Guesthouse Cork, I facilitated regular practice sessions and led a walk in workshop/Asemic session below are some examples of my experiments in Pansemic/Asemic writing.

LETTER TO YOU

BOTTICELLI VENUS

THE UNDERSTORY